he Athens Lunatic Asylum, currently known as The Ridges, permeates the history of Athens, Ohio. Opened in 1874, it greatly impacted the local economy, served as a social recreation site for the community and influenced politics at every level. More than a century of psychiatric care is reflected in the architecture, landscape, and local lore of the facilities. The stories and experiences have become interwoven with the history of Southeastern Ohio and its approach to treating mental illness.

he Athens Lunatic Asylum, currently known as The Ridges, permeates the history of Athens, Ohio. Opened in 1874, it greatly impacted the local economy, served as a social recreation site for the community and influenced politics at every level. More than a century of psychiatric care is reflected in the architecture, landscape, and local lore of the facilities. The stories and experiences have become interwoven with the history of Southeastern Ohio and its approach to treating mental illness.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, one in five Americans currently lives with a mental health condition. Though the original institution closed its doors in 1993 and moved across the river to a more modern location, people in the region continue to be impacted by mental illness. Strong mental health support remains a necessity in the Athens area. Though the people and place have changed, the story continues to be written.

The video below is a poetic adaptation of an anonymously written letter by a former patient of the Athens State Hospital. The letter is believed to be written by a female after 1950.

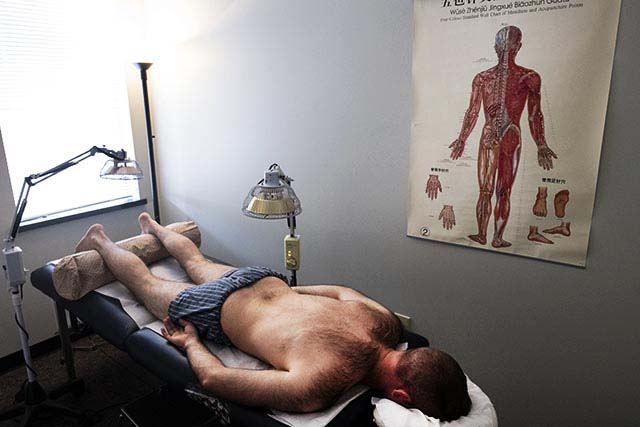

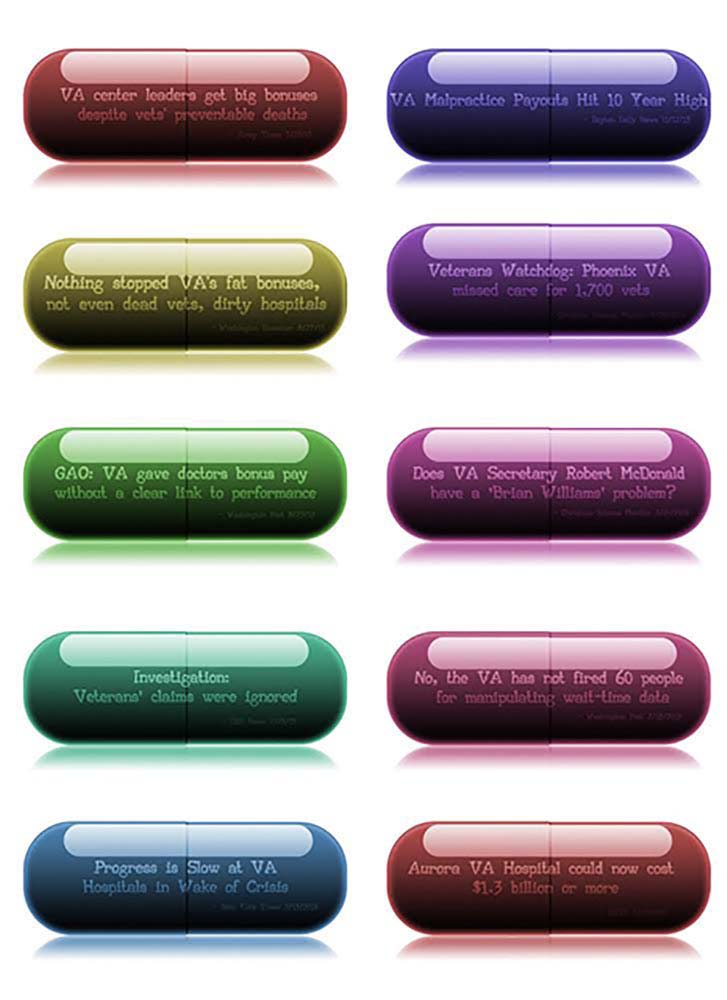

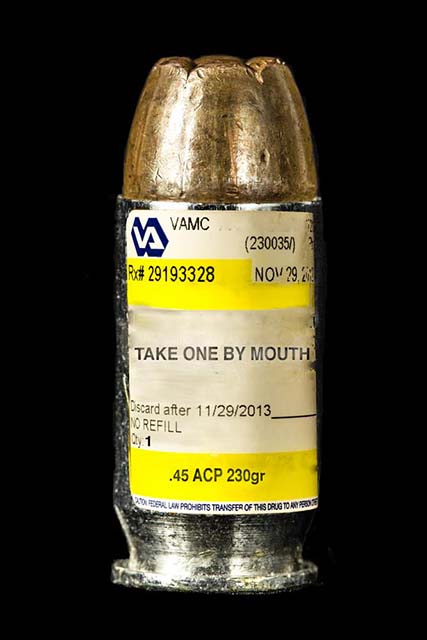

or the most part, Adam Nilson wants to avoid the stigma that comes with being a United States military veteran living with post-traumatic stress disorder and deployment-related injuries. “You feel like no one understands you; you don’t feel close to anybody, and then there are all these misconceptions about what you are and what you aren’t,” says Adam. “So, I really don’t talk about military service to people.”

or the most part, Adam Nilson wants to avoid the stigma that comes with being a United States military veteran living with post-traumatic stress disorder and deployment-related injuries. “You feel like no one understands you; you don’t feel close to anybody, and then there are all these misconceptions about what you are and what you aren’t,” says Adam. “So, I really don’t talk about military service to people.”

hristi Hysell grew up in Meigs County, Ohio. Her home sat on the side of a sloping ridge between the gravel road that ran to the highway and a hilltop where she would sit under her favorite tree to read. She had her ears pierced like other girls, but she was more interested in playing with Tonka Trucks than with dolls and only wore skirts when it was a part of her Girl Scout uniform.

hristi Hysell grew up in Meigs County, Ohio. Her home sat on the side of a sloping ridge between the gravel road that ran to the highway and a hilltop where she would sit under her favorite tree to read. She had her ears pierced like other girls, but she was more interested in playing with Tonka Trucks than with dolls and only wore skirts when it was a part of her Girl Scout uniform.

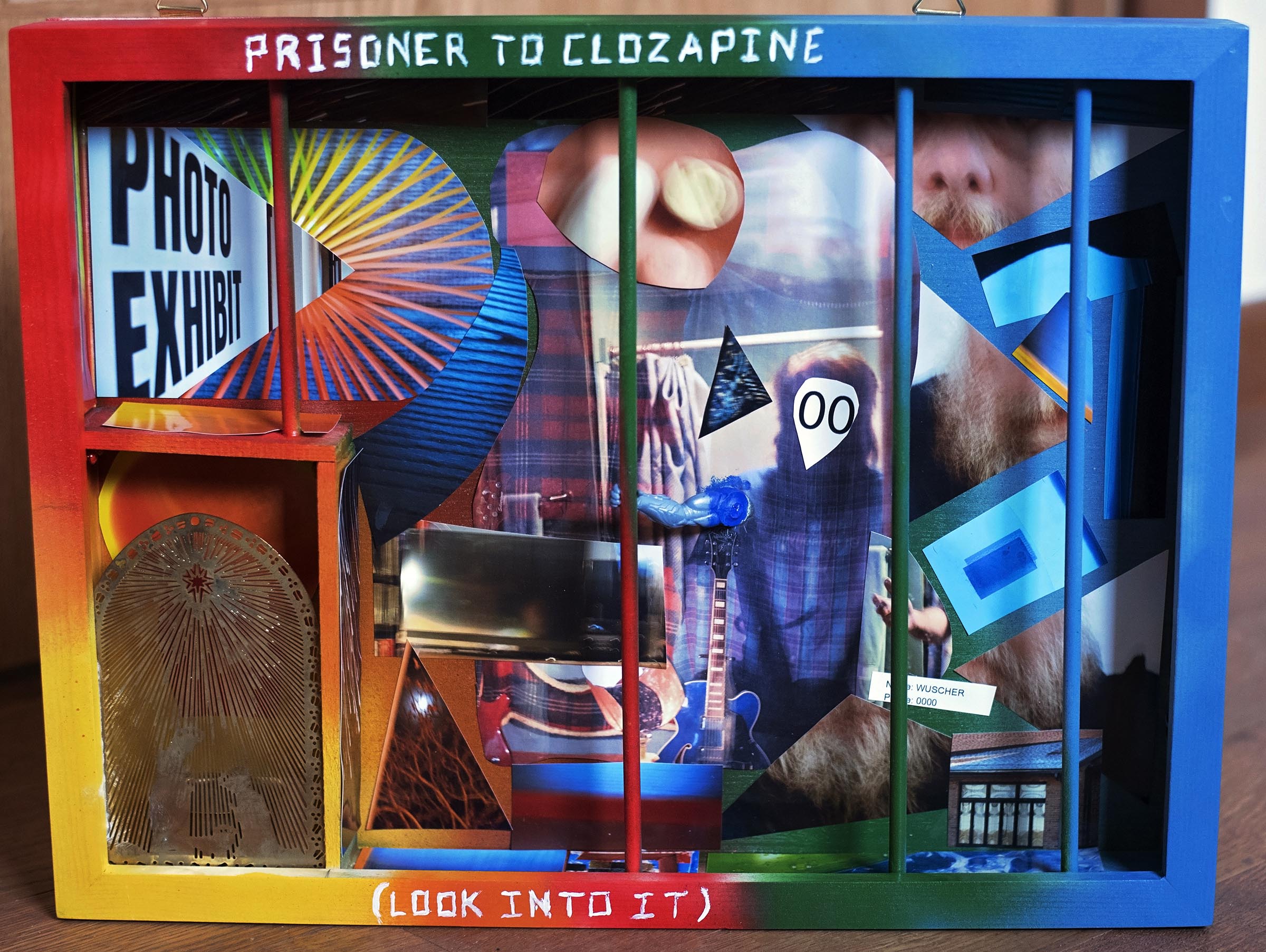

iagnosed with schizophrenia in the late 1980s, Pete Wuscher is no stranger to the mental health system in Athens, Ohio. A self-described “product of the 60s and 70s,” Pete experimented with drugs as a teenager and got into increasingly severe trouble with law enforcement.

iagnosed with schizophrenia in the late 1980s, Pete Wuscher is no stranger to the mental health system in Athens, Ohio. A self-described “product of the 60s and 70s,” Pete experimented with drugs as a teenager and got into increasingly severe trouble with law enforcement.